|

| Bossier Fire Commissioner Fred Jones, Deputy Sheriff Maurice Miller, and Police Officer James C. Cathey, Jr. |

"Preserving the history and memories of Bossier Parish, Louisiana"

Wednesday, January 26, 2022

The Only Major Crime of 1949

Wednesday, August 4, 2021

Fighting Forest Fires in the 1940s

Forestry and forest products are not only a valuable source of income for the state of Louisiana but also for Bossier Parish. The value-added, to Bossier Parish alone, is over fifteen million dollars per year. Value-added represents the creation of new wealth and goes into the economy through payments made to workers, interest, profits, and indirect business taxes.

It goes without saying, the need to protect our forests is a high priority. Research of forest fires began in earnest in the early 1900s on a federal level. By 1940, the Louisiana Forestry Commission was created through an amendment of the Louisiana Constitution. In the early days of the commission, look-out towers, telephone networks, and fire-fighting teams were strategically placed, providing a network of protection for each district in the state.

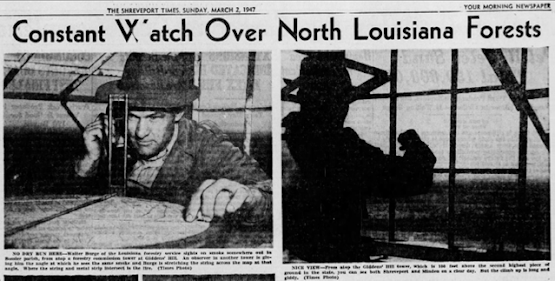

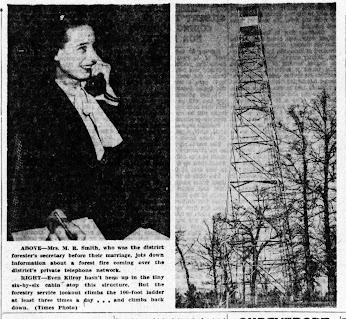

Bossier Parish started with two towers, the Plain Dealing tower near Rocky Mount and the Bodcau tower near Bellevue. The towers were constructed of steel and ranged between 100 and 120 feet tall, depending on the elevation of each location. Atop each tower sat a seven-square-foot observation cabin enclosed in glass on four sides. All of the towers in the fourth district were interconnected by two privately operated telephone lines, which terminated at the district headquarters in Minden.In 1946, a third tower was built on Gidden's Hill, the second-highest point in Louisiana. With Gidden's Hill being 525 feet above sea level, the 100-foot tower, on a clear day, could easily see Shreveport and Minden, and sometimes the Plain Dealing tower and the town of Springhill. A fourth and final tower went up in the Bolinger area in 1948. All of the towers operated 12 months of the year, except the Bolinger tower, which operated for six months of the year.

The fire tower watchmen were on call 24/7 except when there was a lot of rain. They typically lived in a cottage that was on the premises of or very near the tower. Because of this, there was a phone installed at the residence in addition to the tower. A typical day found the watchmen climbing up the 100-foot tower to the observation deck at least three times.

Preventing and squashing forest fires requires a group effort from citizens exercising caution when smoking or making campfires to local fire departments and citizens joining in the fight to extinguish the blaze. After a fire, an investigation takes place to determine the cause and catch those who start fires.The Louisiana Forestry Commission also promoted forestry education among the general public and in schools. Rural schools began establishing school forests and offering forestry programs, such as the Plain Dealing High School Forest, which started in 1946. They also developed nurseries to grow saplings for replanting harvested timberlands, areas destroyed by fire, and planting school forests.

Today, "the Louisiana Office of Forestry is the only state agency with statewide wildland fire-fighting capabilities detected by aircraft or are reported by the public, and are then suppressed by trained forestry crews. It involves approximately 106 wildland firefighters equipped with trucks, tractor-plows and two-way radios. These professional crews are employed year-round. Statistics show that the tractor-plow operator in the southern United States has the most hazardous wildland fire-fighting job in the nation."To learn more about forestry in Bossier Parish, visit the Bossier Parish Libraries History Center at 2206 Beckett Street, Bossier City. Be sure to follow us @BPLHistoryCenter on FB and check out our blog, http://bpl-hc.blogspot.com/. There you will find photographs to go with this article and previous articles. We also have some fun and informative videos on Tiktok; follow @bplhistorycenter to see them.

By: Amy Robertson

Wednesday, January 20, 2021

Barksdale Fire Heroics Recounted

|

| Fire at Barksdale Field, 16 Jan 1945. Source: Barksdale's Bark |

Barksdale Field, now Barksdale Air Force Base, battled its "worst fire disaster in Barksdale's history" during the winter of 1945. Barksdale personnel detected the fire at 3:03 a.m. on a Tuesday, and it raged on for four hours. Before firefighters could extinguish the fire, it leveled hangars one and two along with two twin-engine airplanes. Firefighters remained on the scene as they continued to apply water to the smoldering embers until 10 a.m.

Barksdale firefighters, soldier volunteers, and two Shreveport crews fought the blaze. Col. Garrison, Lt. Col. Grover Wilcox, and Capt. George Booth organized teams of enlisted men and moved planes and equipment from hangar one. "Col. Wilcox and Capt. Booth entered one ship and manned the controls while volunteer soldiers towed it out on the runway. By the time the men reached the plane, it was partially damaged. Capt. Booth's hands were burned in handling the controls of the plane and Col. Wilcox's clothing was scortched [sic]."

The selfless and quick actions of Pvt. Franklin J. Hines made their efforts possible. He single-handedly manned the fire hose's nozzle while perched on a ladder leaning against the burning building when others were driven away by the intense heat. He kept a steady stream of water along the rescue party's path, making it possible for the men to pull the plane from the fire. Also, making it possible for another group of men to remove several gasoline-filled railroad cars sitting nearby.

Hines remained perched precariously on the ladder until he was driven back by the intense heat and smoke. Then he moved to another sector where he and a crew of men continued fighting the fire. Col. Wilcox and Capt. Booth taxied two planes from the parking area facing the fire while enlisted men towed four other aircraft out of the danger zone. Hines’s section officer Lt. Lucien G. Edwards submitted a commendation letter to the 380th headquarters for his heroic actions.

|

| Hangar 1 after the fire. Source: Barksdale's Bark. |

Master Sgt. James J. Flanagan, Sgt. Maj., 331st Base Unit received a commendation "for issuing orders alerting the Base Headquarters staff, and then proceeded to the fire where he assembled approximately 100 enlisted men to move a heavy gasoline truck from the fire area. He also kept spectators away from the buildings until assisted by MP's."

Tech. Sgt. Seth T. Fritz of III TAC received a commendation for "disregarding his own safety, and in the face of imminent danger of exploding gas tanks, he entered a fiercely burning hangar with a fire hose in order to extinguish flames, holding property loss to a minimum. Col. Wright made special mention of the saving made to the government by his gallant action."

The exploding gasoline tanks shot flames into hangar one's roof shortly after the soldiers had rescued the airplane. "Under the intense heat the 3-inch ceilings sagged 14-feet in great bulges before thy [sic] crashed to the floor, dragging large portions of the concrete and steel walls with them." Another plane was pulled to safety just as the roof and hangar doors collapsed. Fighting a fire is always dangerous, but fighting this fire was made more hazardous by machine gun shells exploding in the fire.

|

| The fire ravaged hangars Barksdale Field Jan. 1945. Source: Barksdale's Bark |

Similar heaters in other hangars were removed and replaced with a different type of heating equipment. The concrete slabs where the hangars once stood became a large wash rack—equipped with a large water tank, a solvent solution tank, and pressure hoses. Barksdale used this wash rack to clean B-29s before each 50 and 100-hour inspection and the B-17s 100-hour inspection.

The destroyed airplanes had a value of $758,000, and the hangars had a value of $63,000. The cost would have been far greater without everyone's fast and heroic actions in moving equipment while fighting the fire that night.

By: Amy Robertson