Throughout history there have been many intriguing and mysterious disappearances that remain unsolved such as the Lost Colony of Roanoke, the crew of the Mary Celeste, Amelia Earhart, and the men of Flight 19. One such disappearance has ties to Barksdale Air Force Base, and, although not as well-known as these more famous cases, it nonetheless is still mystifying 74 years after it happened.

In early 1951, the U.S. Air Force’s Strategic Air Command (SAC) established the 7th Air Division and assigned it to England to help counter the growing threat from the Soviet Union. SAC bombers stationed there could serve as a deterrent to Soviet hostilities. Brigadier General Paul Cullen was chosen to command the division and oversee its operations.

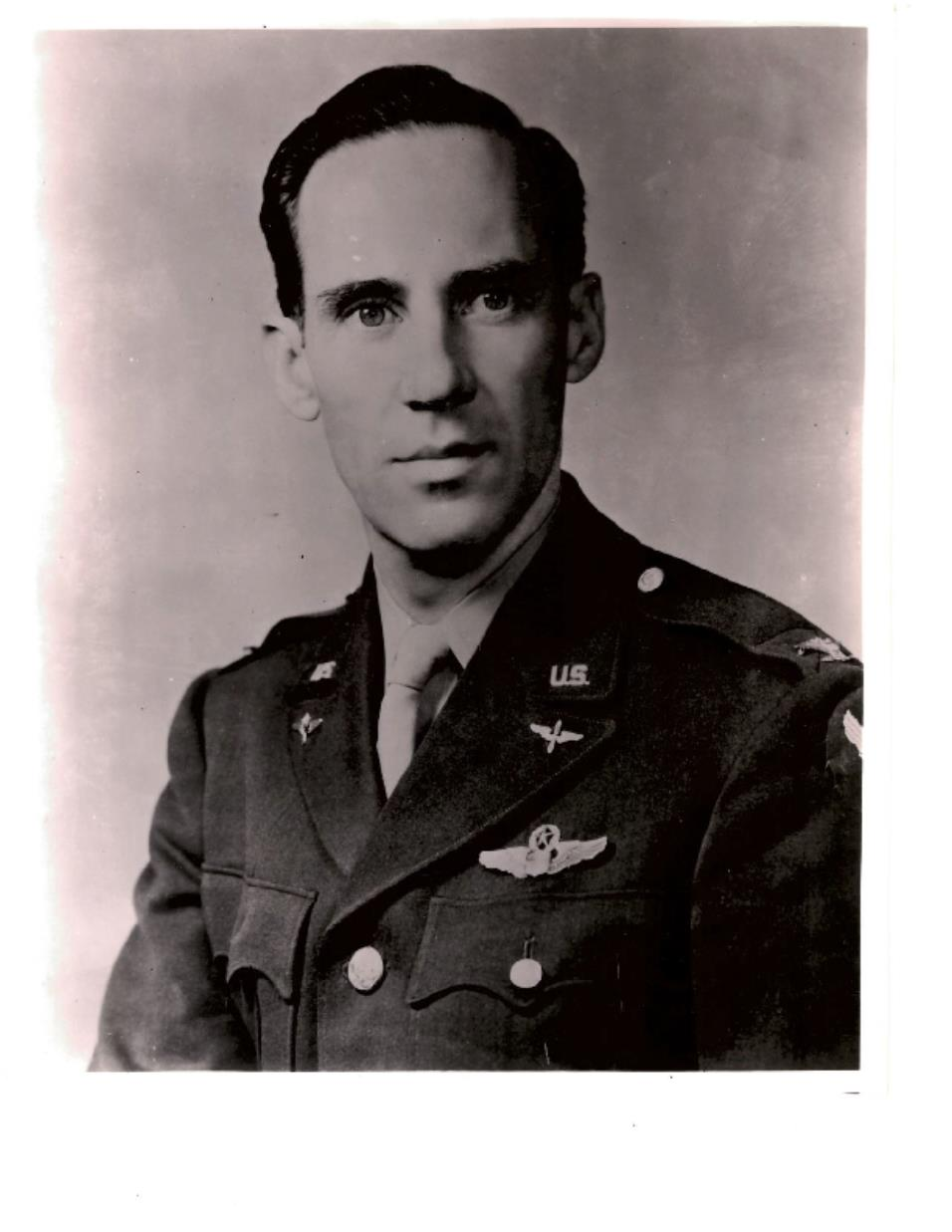

Born in 1901, Cullen joined the military at a time when aviation was still developing. According to his official Air Force biography, he entered service as a flying cadet in June, 1928. Only a year earlier, Charles Lindbergh had become the first person to fly solo, nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. Cullen would become proficient in photo reconnaissance, and his biography states that, among his career achievements, he commanded the Air Force Photo Unit during Operation Crossroads, the atom bomb tests conducted just after World War II.

Cullen’s association with Barksdale came as commander and later vice commander of the 2nd Air Force, which was headquartered at the base beginning in 1949. And it was at Barksdale that Cullen boarded the flight which would carry him and 52 others into the unknown.

The Douglas C-124 Globemaster II departed Walker Air Force Base in Roswell, New Mexico on March 21, 1951 and flew to Barksdale where Brig. Gen. Cullen and his staff joined the other passengers, which included experts in various air defense operations. England was their destination where Cullen would take charge of the 7th. According to Flying Magazine, the Globemaster was an aircraft which “tended to shake a lot, even in calm skies, earning it the nickname ‘Old Shaky.’” It was in these somewhat uncomfortable conditions that the flight made a brief refueling stop in Maine before heading out over the open North Atlantic on Friday, March 23rd. Checking in with weather ships along the route, the flight’s radio operator reported the plane’s position Friday evening as being approximately 800 miles from the coast of Ireland. All seemed to be going well, but that suddenly changed.

An article titled “Last Flight, the Missing Airmen, March 1951” on the Walker Aviation Museum website states that the C-124 gave out a mayday call, reporting a fire in the cargo crates and saying that the plane would have to set down in the ocean. “The aircraft was intact when it touched down,” according to the website. “All hands exited the aircraft wearing life preservers and climbed into inflated 5-man life rafts. The rafts were equipped with cold weather gear, food, water, flares, and … hand-crank emergency radios.” Having survived the forced water landing, the crew and passengers awaited rescue. It came too late.

An Air Force B-29 was sent from England and located the men and circled their position, but had to return to base after running low on fuel. According to the Walker Aviation Museum website, “Not one ship or a single aircraft returned to the position … until Sunday, the 25th of March, 1951.” When help did come, rescuers found nothing other than “some charred crates and a partially deflated life raft,” the website states. The 53 men were gone, vanished without a trace. A search lasting several days proved futile.

Despite the passage of time, answers to the mystery of what happened to Cullen and the others haven’t been forthcoming. Could a sudden storm have created rough seas that swamped the life rafts? Did the Russians, as some have speculated, snatch the men? The website for the Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives states that “… it was revealed that Soviet submarines and surface vessels were active in the area.” The website also notes, “Due to their expertise in nuclear and other defense matters, Cullen and the other men on the airplane would have been an intelligence windfall to the Soviets.”

Questions have been asked about the delay in help arriving. Could the men have been saved if rescue had come sooner? Perhaps one day, we’ll know. Perhaps a long-secret document will come to light that will provide some sense of closure for the men’s families. For now, the “Last Flight” article may sum up the situation best. “We do not know what fate befell these men,” it states.

If you have any photos or other information relating to Bossier Parish history, the History Center may be interested in adding the materials to its research collection by donation or by scanning them and returning the originals. Call or visit us to learn more. We are open M-Th 9-8, Fri 9-6, and Sat 9-5. Our phone number is (318) 746-7717 and our email is history-center@bossierlibrary.org. We can also be found online at https://www.facebook.com/BPLHistoryCenter/ and http://bpl-hc.blogspot.com/

Images:

- Brigadier General Paul Cullen/courtesy United States Air Force

- C-124 Globemaster II/courtesy United States Air Force

No comments:

Post a Comment